Space Shuttle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable

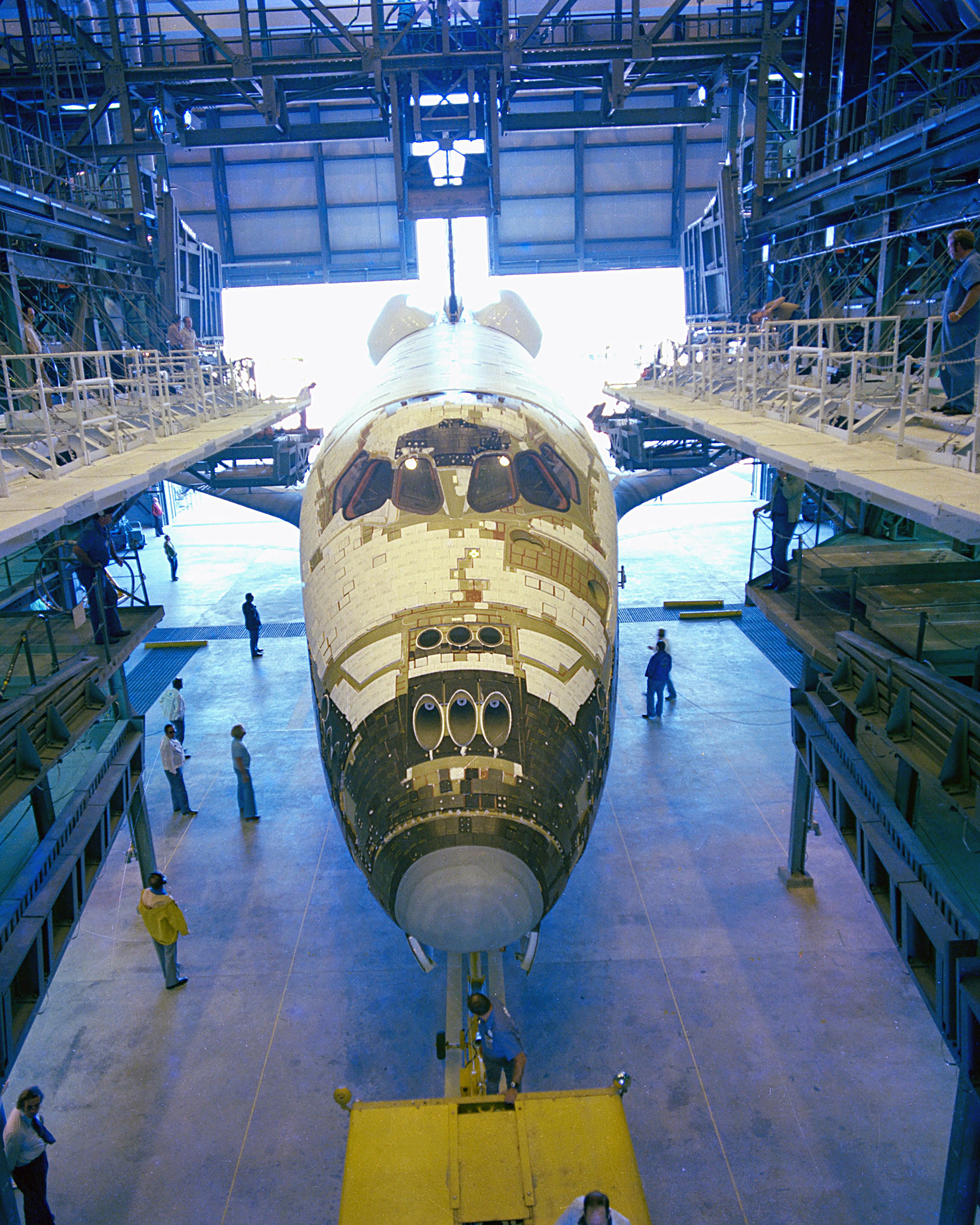

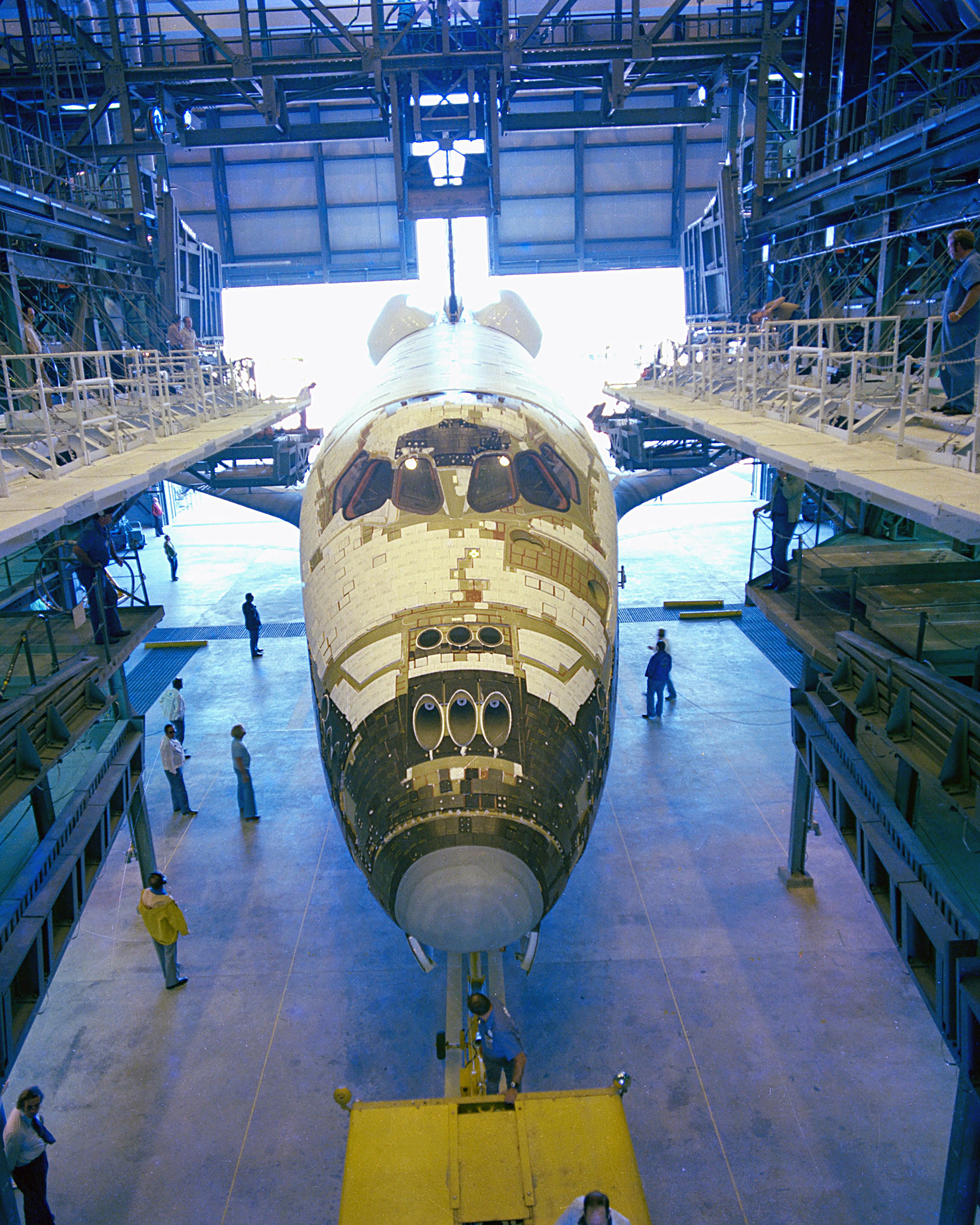

On June 4, 1974, Rockwell began construction on the first orbiter, OV-101, dubbed Constitution, later to be renamed ''Enterprise''. ''Enterprise'' was designed as a test vehicle, and did not include engines or heat shielding. Construction was completed on September 17, 1976, and ''Enterprise'' was moved to the

On June 4, 1974, Rockwell began construction on the first orbiter, OV-101, dubbed Constitution, later to be renamed ''Enterprise''. ''Enterprise'' was designed as a test vehicle, and did not include engines or heat shielding. Construction was completed on September 17, 1976, and ''Enterprise'' was moved to the

After it arrived at Edwards AFB, ''Enterprise'' underwent flight testing with the

After it arrived at Edwards AFB, ''Enterprise'' underwent flight testing with the

The orbiter had design elements and capabilities of both a rocket and an aircraft to allow it to launch vertically and then land as a glider. Its three-part fuselage provided support for the crew compartment, cargo bay, flight surfaces, and engines. The rear of the orbiter contained the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), which provided thrust during launch, as well as the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS), which allowed the orbiter to achieve, alter, and exit its orbit once in space. Its double-

The orbiter had design elements and capabilities of both a rocket and an aircraft to allow it to launch vertically and then land as a glider. Its three-part fuselage provided support for the crew compartment, cargo bay, flight surfaces, and engines. The rear of the orbiter contained the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), which provided thrust during launch, as well as the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS), which allowed the orbiter to achieve, alter, and exit its orbit once in space. Its double-

The flight deck was the top level of the crew compartment and contained the flight controls for the orbiter. The commander sat in the front left seat, and the pilot sat in the front right seat, with two to four additional seats set up for additional crew members. The instrument panels contained over 2,100 displays and controls, and the commander and pilot were both equipped with a

The flight deck was the top level of the crew compartment and contained the flight controls for the orbiter. The commander sat in the front left seat, and the pilot sat in the front right seat, with two to four additional seats set up for additional crew members. The instrument panels contained over 2,100 displays and controls, and the commander and pilot were both equipped with a

The Space Shuttle's

The Space Shuttle's

The payload bay comprised most of the orbiter vehicle's

The payload bay comprised most of the orbiter vehicle's

The Spacelab module was a European-funded pressurized laboratory that was carried within the payload bay and allowed for scientific research while in orbit. The Spacelab module contained two segments that were mounted in the aft end of the payload bay to maintain the center of gravity during flight. Astronauts entered the Spacelab module through a tunnel that connected to the airlock. The Spacelab equipment was primarily stored in pallets, which provided storage for both experiments as well as computer and power equipment. Spacelab hardware was flown on 28 missions through 1999 and studied subjects including astronomy, microgravity, radar, and life sciences. Spacelab hardware also supported missions such as Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing and space station resupply. The Spacelab module was tested on STS-2 and STS-3, and the first full mission was on STS-9.

The Spacelab module was a European-funded pressurized laboratory that was carried within the payload bay and allowed for scientific research while in orbit. The Spacelab module contained two segments that were mounted in the aft end of the payload bay to maintain the center of gravity during flight. Astronauts entered the Spacelab module through a tunnel that connected to the airlock. The Spacelab equipment was primarily stored in pallets, which provided storage for both experiments as well as computer and power equipment. Spacelab hardware was flown on 28 missions through 1999 and studied subjects including astronomy, microgravity, radar, and life sciences. Spacelab hardware also supported missions such as Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing and space station resupply. The Spacelab module was tested on STS-2 and STS-3, and the first full mission was on STS-9.

Three RS-25 engines, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), were mounted on the orbiter's aft fuselage in a triangular pattern. The engine nozzles could gimbal ±10.5° in pitch, and ±8.5° in yaw during ascent to change the direction of their thrust to steer the Shuttle. The

Three RS-25 engines, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), were mounted on the orbiter's aft fuselage in a triangular pattern. The engine nozzles could gimbal ±10.5° in pitch, and ±8.5° in yaw during ascent to change the direction of their thrust to steer the Shuttle. The

The Space Shuttle external tank (ET) carried the propellant for the Space Shuttle Main Engines, and connected the orbiter vehicle with the solid rocket boosters. The ET was tall and in diameter, and contained separate tanks for liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. The liquid oxygen tank was housed in the nose of the ET, and was tall. The liquid hydrogen tank comprised the bulk of the ET, and was tall. The orbiter vehicle was attached to the ET at two umbilical plates, which contained five propellant and two electrical umbilicals, and forward and aft structural attachments. The exterior of the ET was covered in orange spray-on foam to allow it to survive the heat of ascent.

The ET provided propellant to the Space Shuttle Main Engines from liftoff until main engine cutoff. The ET separated from the orbiter vehicle 18 seconds after engine cutoff and could be triggered automatically or manually. At the time of separation, the orbiter vehicle retracted its umbilical plates, and the umbilical cords were sealed to prevent excess propellant from venting into the orbiter vehicle. After the bolts attached at the structural attachments were sheared, the ET separated from the orbiter vehicle. At the time of separation, gaseous oxygen was vented from the nose to cause the ET to tumble, ensuring that it would break up upon reentry. The ET was the only major component of the Space Shuttle system that was not reused, and it would travel along a ballistic trajectory into the Indian or Pacific Ocean.

For the first two missions, STS-1 and

The Space Shuttle external tank (ET) carried the propellant for the Space Shuttle Main Engines, and connected the orbiter vehicle with the solid rocket boosters. The ET was tall and in diameter, and contained separate tanks for liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. The liquid oxygen tank was housed in the nose of the ET, and was tall. The liquid hydrogen tank comprised the bulk of the ET, and was tall. The orbiter vehicle was attached to the ET at two umbilical plates, which contained five propellant and two electrical umbilicals, and forward and aft structural attachments. The exterior of the ET was covered in orange spray-on foam to allow it to survive the heat of ascent.

The ET provided propellant to the Space Shuttle Main Engines from liftoff until main engine cutoff. The ET separated from the orbiter vehicle 18 seconds after engine cutoff and could be triggered automatically or manually. At the time of separation, the orbiter vehicle retracted its umbilical plates, and the umbilical cords were sealed to prevent excess propellant from venting into the orbiter vehicle. After the bolts attached at the structural attachments were sheared, the ET separated from the orbiter vehicle. At the time of separation, gaseous oxygen was vented from the nose to cause the ET to tumble, ensuring that it would break up upon reentry. The ET was the only major component of the Space Shuttle system that was not reused, and it would travel along a ballistic trajectory into the Indian or Pacific Ocean.

For the first two missions, STS-1 and

The Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB) provided 71.4% of the Space Shuttle's thrust during liftoff and ascent, and were the largest solid-propellant motors ever flown. Each SRB was tall and wide, weighed , and had a steel exterior approximately thick. The SRB's subcomponents were the solid-propellant motor, nose cone, and rocket nozzle. The solid-propellant motor comprised the majority of the SRB's structure. Its casing consisted of 11 steel sections which made up its four main segments. The nose cone housed the forward separation motors and the parachute systems that were used during recovery. The rocket nozzles could gimbal up to 8° to allow for in-flight adjustments.

The rocket motors were each filled with a total of solid rocket propellant ( APCP+ PBAN), and joined in the

The Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB) provided 71.4% of the Space Shuttle's thrust during liftoff and ascent, and were the largest solid-propellant motors ever flown. Each SRB was tall and wide, weighed , and had a steel exterior approximately thick. The SRB's subcomponents were the solid-propellant motor, nose cone, and rocket nozzle. The solid-propellant motor comprised the majority of the SRB's structure. Its casing consisted of 11 steel sections which made up its four main segments. The nose cone housed the forward separation motors and the parachute systems that were used during recovery. The rocket nozzles could gimbal up to 8° to allow for in-flight adjustments.

The rocket motors were each filled with a total of solid rocket propellant ( APCP+ PBAN), and joined in the

The Space Shuttle's operations were supported by vehicles and infrastructure that facilitated its transportation, construction, and crew access. The

The Space Shuttle's operations were supported by vehicles and infrastructure that facilitated its transportation, construction, and crew access. The

The Space Shuttle was prepared for launch primarily in the VAB at the KSC. The SRBs were assembled and attached to the external tank on the MLP. The orbiter vehicle was prepared at the

The Space Shuttle was prepared for launch primarily in the VAB at the KSC. The SRBs were assembled and attached to the external tank on the MLP. The orbiter vehicle was prepared at the

The mission crew and the Launch Control Center (LCC) personnel completed systems checks throughout the countdown. Two built-in holds at T−20 minutes and T−9 minutes provided scheduled breaks to address any issues and additional preparation. After the built-in hold at T−9 minutes, the countdown was automatically controlled by the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) at the LCC, which stopped the countdown if it sensed a critical problem with any of the Space Shuttle's onboard systems. At T−3 minutes 45 seconds, the engines began conducting gimbal tests, which were concluded at T−2 minutes 15 seconds. The ground

The mission crew and the Launch Control Center (LCC) personnel completed systems checks throughout the countdown. Two built-in holds at T−20 minutes and T−9 minutes provided scheduled breaks to address any issues and additional preparation. After the built-in hold at T−9 minutes, the countdown was automatically controlled by the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) at the LCC, which stopped the countdown if it sensed a critical problem with any of the Space Shuttle's onboard systems. At T−3 minutes 45 seconds, the engines began conducting gimbal tests, which were concluded at T−2 minutes 15 seconds. The ground  Beginning at T−6.6 seconds, the main engines were ignited sequentially at 120-millisecond intervals. All three RS-25 engines were required to reach 90% rated thrust by T−3 seconds, otherwise the GPCs would initiate an RSLS abort. If all three engines indicated nominal performance by T−3 seconds, they were commanded to gimbal to liftoff configuration and the command would be issued to arm the SRBs for ignition at T−0. Between T−6.6 seconds and T−3 seconds, while the RS-25 engines were firing but the SRBs were still bolted to the pad, the offset thrust would cause the Space Shuttle to pitch down measured at the tip of the external tank; the 3-second delay allowed the stack to return to nearly vertical before SRB ignition. This movement was nicknamed the "twang." At T−0, the eight frangible nuts holding the SRBs to the pad were detonated, the final umbilicals were disconnected, the SSMEs were commanded to 100% throttle, and the SRBs were ignited. By T+0.23 seconds, the SRBs built up enough thrust for liftoff to commence, and reached maximum chamber pressure by T+0.6 seconds. At T−0, the JSC

Beginning at T−6.6 seconds, the main engines were ignited sequentially at 120-millisecond intervals. All three RS-25 engines were required to reach 90% rated thrust by T−3 seconds, otherwise the GPCs would initiate an RSLS abort. If all three engines indicated nominal performance by T−3 seconds, they were commanded to gimbal to liftoff configuration and the command would be issued to arm the SRBs for ignition at T−0. Between T−6.6 seconds and T−3 seconds, while the RS-25 engines were firing but the SRBs were still bolted to the pad, the offset thrust would cause the Space Shuttle to pitch down measured at the tip of the external tank; the 3-second delay allowed the stack to return to nearly vertical before SRB ignition. This movement was nicknamed the "twang." At T−0, the eight frangible nuts holding the SRBs to the pad were detonated, the final umbilicals were disconnected, the SSMEs were commanded to 100% throttle, and the SRBs were ignited. By T+0.23 seconds, the SRBs built up enough thrust for liftoff to commence, and reached maximum chamber pressure by T+0.6 seconds. At T−0, the JSC  At T+4 seconds, when the Space Shuttle reached an altitude of , the RS-25 engines were throttled up to 104.5%. At approximately T+7 seconds, the Space Shuttle rolled to a heads-down orientation at an altitude of , which reduced aerodynamic stress and provided an improved communication and navigation orientation. Approximately 20–30 seconds into ascent and an altitude of , the RS-25 engines were throttled down to 65–72% to reduce the maximum aerodynamic forces at Max Q. Additionally, the shape of the SRB propellant was designed to cause thrust to decrease at the time of Max Q. The GPCs could dynamically control the throttle of the RS-25 engines based upon the performance of the SRBs.

At T+4 seconds, when the Space Shuttle reached an altitude of , the RS-25 engines were throttled up to 104.5%. At approximately T+7 seconds, the Space Shuttle rolled to a heads-down orientation at an altitude of , which reduced aerodynamic stress and provided an improved communication and navigation orientation. Approximately 20–30 seconds into ascent and an altitude of , the RS-25 engines were throttled down to 65–72% to reduce the maximum aerodynamic forces at Max Q. Additionally, the shape of the SRB propellant was designed to cause thrust to decrease at the time of Max Q. The GPCs could dynamically control the throttle of the RS-25 engines based upon the performance of the SRBs.

At approximately T+123 seconds and an altitude of , pyrotechnic fasteners released the SRBs, which reached an

At approximately T+123 seconds and an altitude of , pyrotechnic fasteners released the SRBs, which reached an

The type of mission the Space Shuttle was assigned to dictate the type of orbit that it entered. The initial design of the reusable Space Shuttle envisioned an increasingly cheap launch platform to deploy commercial and government satellites. Early missions routinely ferried satellites, which determined the type of orbit that the orbiter vehicle would enter. Following the ''Challenger'' disaster, many commercial payloads were moved to expendable commercial rockets, such as the

The type of mission the Space Shuttle was assigned to dictate the type of orbit that it entered. The initial design of the reusable Space Shuttle envisioned an increasingly cheap launch platform to deploy commercial and government satellites. Early missions routinely ferried satellites, which determined the type of orbit that the orbiter vehicle would enter. Following the ''Challenger'' disaster, many commercial payloads were moved to expendable commercial rockets, such as the

Approximately four hours prior to deorbit, the crew began preparing the orbiter vehicle for reentry by closing the payload doors, radiating excess heat, and retracting the Ku band antenna. The orbiter vehicle maneuvered to an upside-down, tail-first orientation and began a 2–4 minute OMS burn approximately 20 minutes before it reentered the atmosphere. The orbiter vehicle reoriented itself to a nose-forward position with a 40° angle-of-attack, and the forward

Approximately four hours prior to deorbit, the crew began preparing the orbiter vehicle for reentry by closing the payload doors, radiating excess heat, and retracting the Ku band antenna. The orbiter vehicle maneuvered to an upside-down, tail-first orientation and began a 2–4 minute OMS burn approximately 20 minutes before it reentered the atmosphere. The orbiter vehicle reoriented itself to a nose-forward position with a 40° angle-of-attack, and the forward  The approach and landing phase began when the orbiter vehicle was at an altitude of and traveling at . The orbiter followed either a 20° or 18° glideslope and descended at approximately . The speed brake was used to keep a continuous speed, and crew initiated a pre-flare maneuver to a 1.5° glideslope at an altitude of . The landing gear was deployed 10 seconds prior to touchdown, when the orbiter was at an altitude of and traveling . A final flare maneuver reduced the orbiter vehicle's descent rate to , with touchdown occurring at , depending on the weight of the orbiter vehicle. After the landing gear touched down, the crew deployed a drag chute out of the vertical stabilizer, and began wheel braking when the orbiter was traveling slower than . After the orbiter's wheels stopped, the crew deactivated the flight components and prepared to exit.

The approach and landing phase began when the orbiter vehicle was at an altitude of and traveling at . The orbiter followed either a 20° or 18° glideslope and descended at approximately . The speed brake was used to keep a continuous speed, and crew initiated a pre-flare maneuver to a 1.5° glideslope at an altitude of . The landing gear was deployed 10 seconds prior to touchdown, when the orbiter was at an altitude of and traveling . A final flare maneuver reduced the orbiter vehicle's descent rate to , with touchdown occurring at , depending on the weight of the orbiter vehicle. After the landing gear touched down, the crew deployed a drag chute out of the vertical stabilizer, and began wheel braking when the orbiter was traveling slower than . After the orbiter's wheels stopped, the crew deactivated the flight components and prepared to exit.

After the landing, ground crews approached the orbiter to conduct safety checks. Teams wearing self-contained breathing gear tested for the presence of

After the landing, ground crews approached the orbiter to conduct safety checks. Teams wearing self-contained breathing gear tested for the presence of

low Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an geocentric orbit, orbit around Earth with a orbital period, period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an orbital eccentricity, eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial object ...

al spacecraft system

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, planetary exploration, ...

operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the United States's civil space program, aeronautics research and space research. Established in 1958, it su ...

(NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its ...

. Its official program name was the Space Transportation System

The Space Transportation System (STS), also known internally to NASA as the Integrated Program Plan (IPP), was a proposed system of reusable crewed spacecraft, space vehicles envisioned in 1969 to support extended operations beyond the Apollo ...

(STS), taken from the 1969 plan led by U.S. vice president Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

for a system of reusable spacecraft where it was the only item funded for development.

The first (STS-1

STS-1 (Space Transportation System-1) was the first orbital spaceflight of NASA's Space Shuttle program. The first orbiter, ''Columbia'', launched on April 12, 1981, and returned on April 14, 1981, 54.5 hours later, having orbited the Earth 3 ...

) of four orbital test flights occurred in 1981, leading to operational flights (STS-5

STS-5 was the fifth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the fifth flight of the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. It launched on November 11, 1982, and landed five days later on November 16, 1982. STS-5 was the first Space Shuttle mission to deploy comm ...

) beginning in 1982. Five complete Space Shuttle orbiter vehicles were built and flown on a total of 135 missions from 1981 to 2011. They launched from the Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the NASA, National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten NASA facilities#List of field c ...

(KSC) in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

. Operational missions launched numerous satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scient ...

s, interplanetary probes, and the Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the Orbiting Solar Observatory, first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most ...

(HST), conducted science experiments in orbit, participated in the Shuttle-''Mir'' program with Russia, and participated in the construction and servicing of the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a large space station that was Assembly of the International Space Station, assembled and is maintained in low Earth orbit by a collaboration of five space agencies and their contractors: NASA (United ...

(ISS). The Space Shuttle fleet's total mission time was 1,323 days.

Space Shuttle components include the Orbiter Vehicle (OV) with three clustered Rocketdyne

Rocketdyne is an American rocket engine design and production company headquartered in Canoga Park, California, Canoga Park, in the western San Fernando Valley of suburban Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles, in southern California.

Rocketdyne ...

RS-25

The RS-25, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME), is a liquid-fuel cryogenic rocket engine that was used on NASA's Space Shuttle and is used on the Space Launch System.

Designed and manufactured in the United States by Rocketd ...

main engines, a pair of recoverable solid rocket boosters

A solid rocket booster (SRB) is a solid propellant motor used to provide thrust in spacecraft launches from initial launch through the first ascent. Many launch vehicles, including the Atlas V, SLS and Space Shuttle, have used SRBs to give launch ...

(SRBs), and the expendable external tank

The Space Shuttle external tank (ET) was the component of the Space Shuttle launch vehicle that contained the liquid hydrogen Rocket propellant, fuel and liquid oxygen oxidizer. During lift-off and ascent it supplied the fuel and oxidizer und ...

(ET) containing liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen () is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecule, molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point (thermodynamics), critical point of 33 Kelvins, ...

and liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen, sometimes abbreviated as LOX or LOXygen, is a clear cyan liquid form of dioxygen . It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an application which is ongoing.

Physical ...

. The Space Shuttle was launched vertically, like a conventional rocket, with the two SRBs operating in parallel with the orbiter's three main engines, which were fueled from the ET. The SRBs were jettisoned before the vehicle reached orbit, while the main engines continued to operate, and the ET was jettisoned after main engine cutoff and just before orbit insertion

In spaceflight an orbit insertion is an orbital maneuver which adjusts a spacecraft’s trajectory, allowing entry into an orbit around a planet, moon, or other celestial body, becoming an artificial satellite. An orbiter is a spacecraft designed ...

, which used the orbiter's two Orbital Maneuvering System

In spaceflight, an orbital maneuver (otherwise known as a burn) is the use of propulsion systems to change the orbit of a spacecraft.

For spacecraft far from Earth, an orbital maneuver is called a ''deep-space maneuver (DSM)''.

When a spacec ...

(OMS) engines. At the conclusion of the mission, the orbiter fired its OMS to deorbit and reenter the atmosphere. The orbiter was protected during reentry by its thermal protection system

Atmospheric entry (sometimes listed as Vimpact or Ventry) is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. Atmospheric entry may be ''uncontrolled entr ...

tiles, and it glided as a spaceplane

A spaceplane is a vehicle that can flight, fly and gliding flight, glide as an aircraft in Earth's atmosphere and function as a spacecraft in outer space. To do so, spaceplanes must incorporate features of both aircraft and spacecraft. Orbit ...

to a runway landing, usually to the Shuttle Landing Facility

The Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF), also known as Launch and Landing Facility (LLF) , is an airport located on Merritt Island, Florida, Merritt Island in Brevard County, Florida, Brevard County, Florida, United States. It is a part of the Kennedy ...

at KSC, Florida, or to Rogers Dry Lake

Rogers Dry Lake is an endorheic desert salt pan in the Mojave Desert of Kern County, California. The lake derives its name from the Anglicization from the Spanish name, Rodriguez Dry Lake. It is the central part of Edwards Air Force Base as its ...

in Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation in California. Most of the base sits in Kern County, California, Kern County, but its eastern end is in San Bernardino County, California, San Bernardino County and a souther ...

, California. If the landing occurred at Edwards, the orbiter was flown back to the KSC atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) are two extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters. One (N905NA) is a 747-100 model, while the other (N911NA) is a short-range 747-100SR. Both are now retired. ...

(SCA), a specially modified Boeing 747

The Boeing 747 is a long-range wide-body aircraft, wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2023.

After the introduction of the Boeing 707, 707 in October 1958, Pan Am ...

designed to carry the shuttle above it.

The first orbiter, ''Enterprise

Enterprise (or the archaic spelling Enterprize) may refer to:

Business and economics

Brands and enterprises

* Enterprise GP Holdings, an energy holding company

* Enterprise plc, a UK civil engineering and maintenance company

* Enterpris ...

'', was built in 1976 and used in Approach and Landing Tests

The Approach and Landing Tests were a series of sixteen taxiing, taxi and flight trials of the prototype Space Shuttle Orbiter, Space Shuttle ''Space Shuttle Enterprise, Enterprise'' that took place between February and October 1977 to test the ...

(ALT), but had no orbital capability. Four fully operational orbiters were initially built: '' Columbia'', '' Challenger'', ''Discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discovery ...

'', and ''Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

''. Of these, two were lost in mission accidents: ''Challenger'' in 1986 and ''Columbia'' in 2003, with a total of 14 astronauts killed. A fifth operational (and sixth in total) orbiter, '' Endeavour'', was built in 1991 to replace ''Challenger''. The three surviving operational vehicles were retired from service following ''Atlantis''s final flight on July 21, 2011. The U.S. relied on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft

Soyuz () is a series of spacecraft which has been in service since the 1960s, having made more than 140 flights. It was designed for the Soviet space program by the Korolev Design Bureau (now Energia). The Soyuz succeeded the Voskhod spacecraf ...

to transport astronauts to the ISS from the last Shuttle flight until the launch of the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission in May 2020.

Design and development

Historical background

In the late 1930s, the German government launched the "Amerikabomber

The ''Amerikabomber'' () project was an initiative of the German Ministry of Aviation (''Reichsluftfahrtministerium'') to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the ''Luftwaffe'' that would be capable of striking the United States (specificall ...

" (English: America bomber) project, and Eugen Sanger's idea, together with mathematician Irene Bredt, was a winged rocket called the Silbervogel

Silbervogel (German for "silver bird") was a design for a liquid-propellant rocket-powered sub-orbital bomber produced by Eugen Sänger and Irene Bredt in the late 1930s for The Third Reich. It is also known as the RaBo ( – "rocket bomber"). ...

(German for "silver bird"). During the 1950s, the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

proposed using a reusable piloted glider to perform military operations such as reconnaissance, satellite attack, and air-to-ground weapons employment. In the late 1950s, the Air Force began developing the partially reusable X-20 Dyna-Soar. The Air Force collaborated with NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

on the Dyna-Soar and began training six pilots in June 1961. The rising costs of development and the prioritization of Project Gemini

Project Gemini () was the second United States human spaceflight program to fly. Conducted after the first American crewed space program, Project Mercury, while the Apollo program was still in early development, Gemini was conceived in 1961 and ...

led to the cancellation of the Dyna-Soar program in December 1963. In addition to the Dyna-Soar, the Air Force had conducted a study in 1957 to test the feasibility of reusable boosters. This became the basis for the aerospaceplane, a fully reusable spacecraft that was never developed beyond the initial design phase in 1962–1963.

Beginning in the early 1950s, NASA and the Air Force collaborated on developing lifting bodies

A lifting body is a fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using aerodynamic lift. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct from rotary-wing aircraft (in which a ...

to test aircraft that primarily generated lift from their fuselages instead of wings, and tested the NASA M2-F1

The NASA M2-F1 is a lightweight, unpowered prototype aircraft, developed to flight-test the wingless lifting body concept. Its unusual appearance earned it the nickname "flying bathtub" and was designated the M2-F1, the M referring to "manned", ...

, Northrop M2-F2

The Northrop M2-F2 was a heavyweight lifting body based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers and built by the Northrop Corporation in 1966.

Development

The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and cons ...

, Northrop M2-F3

The Northrop M2-F3 is a heavyweight lifting body rebuilt from the Northrop M2-F2 after it crashed at the Dryden Flight Research Center in 1967. It was modified with an additional third vertical fin - centered between the tip fins - to improve co ...

, Northrop HL-10

The Northrop HL-10 is one of five US heavyweight lifting body designs flown at NASA's Flight Research Center (FRC—later Dryden Flight Research Center) in Edwards, California, from July 1966 to November 1975 to study and validate the concept ...

, Martin Marietta X-24A

The Martin Marietta X-24 is an American experimental aircraft developed from a joint United States Air Force–NASA program named PILOT (1963–1975). It was designed and built to test lifting body concepts, experimenting with the concept of ...

, and the Martin Marietta X-24B Martin may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Europe

* Martin, Croatia, a village

* Martin, Slovakia, a city

* Martín del Río, Aragón, Spain

* Mart ...

. The program tested aerodynamic characteristics that would later be incorporated in design of the Space Shuttle, including unpowered landing from a high altitude and speed.

Design process

On September 24, 1966, as the Apollo space program neared its design completion, NASA and the Air Force released a joint study concluding that a new vehicle was required to satisfy their respective future demands and that a partially reusable system would be the most cost-effective solution. The head of the NASA Office of Manned Space Flight, George Mueller, announced the plan for a reusable shuttle on August 10, 1968. NASA issued a request for proposal (RFP) for designs of the Integral Launch and Reentry Vehicle (ILRV) on October 30, 1968. Rather than award a contract based upon initial proposals, NASA announced a phased approach for the Space Shuttle contracting and development; Phase A was a request for studies completed by competing aerospace companies, Phase B was a competition between two contractors for a specific contract, Phase C involved designing the details of the spacecraft components, and Phase D was the production of the spacecraft. In December 1968, NASA created the Space Shuttle Task Group to determine the optimal design for a reusable spacecraft, and issued study contracts toGeneral Dynamics

General Dynamics Corporation (GD) is an American publicly traded aerospace and defense corporation headquartered in Reston, Virginia. As of 2020, it was the fifth largest defense contractor in the world by arms sales and fifth largest in the Unit ...

, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas

McDonnell Douglas Corporation was a major American Aerospace manufacturer, aerospace manufacturing corporation and defense contractor, formed by the merger of McDonnell Aircraft and the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1967. Between then and its own ...

, and North American Rockwell

North American Aviation (NAA) was a major American aerospace manufacturer that designed and built several notable aircraft and spacecraft. Its products included the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the F- ...

. In July 1969, the Space Shuttle Task Group issued a report that determined the Shuttle would support short-duration crewed missions and space station, as well as the capabilities to launch, service, and retrieve satellites. The report also created three classes of a future reusable shuttle: Class I would have a reusable orbiter mounted on expendable boosters, Class II would use multiple expendable rocket engines and a single propellant tank (stage-and-a-half), and Class III would have both a reusable orbiter and a reusable booster. In September 1969, the Space Task Group, under the leadership of U.S. vice president Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

, issued a report calling for the development of a space shuttle to bring people and cargo to low Earth orbit (LEO), as well as a space tug

''Space Tug'' is a young adult fiction, young adult science fiction novel by author Murray Leinster. It was published in 1953 in literature, 1953 by Shasta Publishers in an edition of 5,000 copies. It is the second novel in the author's Joe K ...

for transfers between orbits and the Moon, and a reusable nuclear upper stage for deep space travel.

After the release of the Space Shuttle Task Group report, many aerospace engineers favored the Class III, fully reusable design because of perceived savings in hardware costs. Max Faget

Maxime Allen "Max" Faget (pronounced ''fah-ZHAY''; August 26, 1921 – October 9, 2004) was an American mechanical engineer. Faget was the designer of the Mercury spacecraft, and contributed to the later Gemini and Apollo spacecraft as wel ...

, a NASA engineer who had worked to design the Mercury capsule, patented a design for a two-stage fully recoverable system with a straight-winged orbiter mounted on a larger straight-winged booster. The Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory argued that a straight-wing design would not be able to withstand the high thermal and aerodynamic stresses during reentry, and would not provide the required cross-range capability. Additionally, the Air Force required a larger payload capacity than Faget's design allowed. In January 1971, NASA and Air Force leadership decided that a reusable delta-wing orbiter mounted on an expendable propellant tank would be the optimal design for the Space Shuttle.

After they established the need for a reusable, heavy-lift spacecraft, NASA and the Air Force determined the design requirements of their respective services. The Air Force expected to use the Space Shuttle to launch large satellites, and required it to be capable of lifting to an eastward LEO or into a polar orbit

A polar orbit is one in which a satellite passes above or nearly above both poles of the body being orbited (usually a planet such as the Earth, but possibly another body such as the Moon or Sun) on each revolution. It has an inclination of abo ...

. The satellite designs also required that the Space Shuttle have a payload bay. NASA evaluated the F-1 and J-2 engines from the Saturn rockets, and determined that they were insufficient for the requirements of the Space Shuttle; in July 1971, it issued a contract to Rocketdyne

Rocketdyne is an American rocket engine design and production company headquartered in Canoga Park, California, Canoga Park, in the western San Fernando Valley of suburban Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles, in southern California.

Rocketdyne ...

to begin development on the RS-25

The RS-25, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME), is a liquid-fuel cryogenic rocket engine that was used on NASA's Space Shuttle and is used on the Space Launch System.

Designed and manufactured in the United States by Rocketd ...

engine.

NASA reviewed 29 potential designs for the Space Shuttle and determined that a design with two side boosters should be used, and the boosters should be reusable to reduce costs. NASA and the Air Force elected to use solid-propellant boosters because of the lower costs and the ease of refurbishing them for reuse after they landed in the ocean. In January 1972, President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

approved the Shuttle, and NASA decided on its final design in March. The development of the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) remained the responsibility of Rocketdyne, and the contract was issued in July 1971, and updated SSME specifications were submitted to Rocketdyne that April. The following August, NASA awarded the contract to build the orbiter to North American Rockwell, which had by then constructed a full-scale mock-up, later named '' Inspiration''. In August 1973, NASA awarded the external tank contract to Martin Marietta

The Martin Marietta Corporation was an American company founded in 1961 through the merger of Glenn L. Martin Company and American-Marietta Corporation. In 1995, it merged with Lockheed Corporation to form Lockheed Martin.

History

Martin Marie ...

, and in November the solid-rocket booster contract to Morton Thiokol.

Development

On June 4, 1974, Rockwell began construction on the first orbiter, OV-101, dubbed Constitution, later to be renamed ''Enterprise''. ''Enterprise'' was designed as a test vehicle, and did not include engines or heat shielding. Construction was completed on September 17, 1976, and ''Enterprise'' was moved to the

On June 4, 1974, Rockwell began construction on the first orbiter, OV-101, dubbed Constitution, later to be renamed ''Enterprise''. ''Enterprise'' was designed as a test vehicle, and did not include engines or heat shielding. Construction was completed on September 17, 1976, and ''Enterprise'' was moved to the Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation in California. Most of the base sits in Kern County, California, Kern County, but its eastern end is in San Bernardino County, California, San Bernardino County and a souther ...

to begin testing. Rockwell constructed the Main Propulsion Test Article (MPTA)-098, which was a structural truss mounted to the ET with three RS-25 engines attached. It was tested at the National Space Technology Laboratory (NSTL) to ensure that the engines could safely run through the launch profile. Rockwell conducted mechanical and thermal stress tests on Structural Test Article (STA)-099 to determine the effects of aerodynamic and thermal stresses during launch and reentry.

The beginning of the development of the RS-25 Space Shuttle Main Engine was delayed for nine months while Pratt & Whitney

Pratt & Whitney is an American aerospace manufacturer with global service operations. It is a subsidiary of RTX Corporation (formerly Raytheon Technologies). Pratt & Whitney's aircraft engines are widely used in both civil aviation (especially ...

challenged the contract that had been issued to Rocketdyne. The first engine was completed in March 1975, after issues with developing the first throttleable, reusable engine. During engine testing, the RS-25 experienced multiple nozzle failures, as well as broken turbine blades. Despite the problems during testing, NASA ordered the nine RS-25 engines needed for its three orbiters under construction in May 1978.

NASA experienced significant delays in the development of the Space Shuttle's thermal protection system

Atmospheric entry (sometimes listed as Vimpact or Ventry) is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. Atmospheric entry may be ''uncontrolled entr ...

. Previous NASA spacecraft had used ablative

In grammar, the ablative case (pronounced ; abbreviated ) is a grammatical case for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the grammars of various languages. It is used to indicate motion away from something, make comparisons, and serve various o ...

heat shields, but those could not be reused. NASA chose to use ceramic tiles for thermal protection, as the shuttle could then be constructed of lightweight aluminum

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

, and the tiles could be individually replaced as needed. Construction began on ''Columbia'' on March 27, 1975, and it was delivered to the KSC on March 25, 1979. At the time of its arrival at the KSC, ''Columbia'' still had 6,000 of its 30,000 tiles remaining to be installed. However, many of the tiles that had been originally installed had to be replaced, requiring two years of installation before ''Columbia'' could fly.

On January 5, 1979, NASA commissioned a second orbiter. Later that month, Rockwell began converting STA-099 to OV-099, later named ''Challenger''. On January 29, 1979, NASA ordered two additional orbiters, OV-103 and OV-104, which were named ''Discovery'' and ''Atlantis''. Construction of OV-105, later named ''Endeavour'', began in February 1982, but NASA decided to limit the Space Shuttle fleet to four orbiters in 1983. After the loss of ''Challenger'', NASA resumed production of ''Endeavour'' in September 1987.

Testing

After it arrived at Edwards AFB, ''Enterprise'' underwent flight testing with the

After it arrived at Edwards AFB, ''Enterprise'' underwent flight testing with the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) are two extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters. One (N905NA) is a 747-100 model, while the other (N911NA) is a short-range 747-100SR. Both are now retired. ...

, a Boeing 747 that had been modified to carry the orbiter. In February 1977, ''Enterprise'' began the Approach and Landing Tests

The Approach and Landing Tests were a series of sixteen taxiing, taxi and flight trials of the prototype Space Shuttle Orbiter, Space Shuttle ''Space Shuttle Enterprise, Enterprise'' that took place between February and October 1977 to test the ...

(ALT) and underwent captive flights, where it remained attached to the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft for the duration of the flight. On August 12, 1977, ''Enterprise'' conducted its first glide test, where it detached from the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and landed at Edwards AFB. After four additional flights, ''Enterprise'' was moved to the Marshall Space Flight Center

Marshall Space Flight Center (officially the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center; MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville postal address), is the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government's ...

(MSFC) on March 13, 1978. ''Enterprise'' underwent shake tests in the Mated Vertical Ground Vibration Test, where it was attached to an external tank and solid rocket boosters, and underwent vibrations to simulate the stresses of launch. In April 1979, ''Enterprise'' was taken to the KSC, where it was attached to an external tank and solid rocket boosters, and moved to LC-39. Once installed at the launch pad, the Space Shuttle was used to verify the proper positioning of the launch complex hardware. ''Enterprise'' was taken back to California in August 1979, and later served in the development of the SLC-6 at Vandenberg AFB

Vandenberg Space Force Base , previously Vandenberg Air Force Base, is a United States Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County, California. Established in 1941, Vandenberg Space Force Base is a space launch base, launching spacecraft from the ...

in 1984.

On November 24, 1980, ''Columbia'' was mated with its external tank and solid-rocket boosters, and was moved to LC-39 on December 29. The first Space Shuttle mission, STS-1

STS-1 (Space Transportation System-1) was the first orbital spaceflight of NASA's Space Shuttle program. The first orbiter, ''Columbia'', launched on April 12, 1981, and returned on April 14, 1981, 54.5 hours later, having orbited the Earth 3 ...

, would be the first time NASA performed a crewed first-flight of a spacecraft. On April 12, 1981, the Space Shuttle launched for the first time, and was piloted by John Young and Robert Crippen. During the two-day mission, Young and Crippen tested equipment on board the shuttle, and found several of the ceramic tiles had fallen off the top side of the ''Columbia''. NASA coordinated with the Air Force to use satellites to image the underside of ''Columbia'', and determined there was no damage. ''Columbia'' reentered the atmosphere and landed at Edwards AFB on April 14.

NASA conducted three additional test flights with ''Columbia'' in 1981 and 1982. On July 4, 1982, STS-4

STS-4 was the fourth NASA Space Shuttle mission, and also the fourth for Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. Crewed by Ken Mattingly and Henry Hartsfield, the mission launched on June 27, 1982, and landed a week later on July 4, 1982. Due to parachut ...

, flown by Ken Mattingly

Thomas Kenneth Mattingly II (March 17, 1936 – October 31, 2023) was an American Naval aviator (United States), aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, Rear admiral (United States), rear admiral in the United States Navy, and astronaut who ...

and Henry Hartsfield

Henry Warren Hartsfield Jr. (November 21, 1933 – July 17, 2014) was a United States Air Force Colonel and NASA astronaut who logged over 480 hours in space. He was inducted into the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2006.

Personal data ...

, landed on a concrete runway at Edwards AFB. President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and his wife Nancy met the crew, and delivered a speech. After STS-4, NASA declared its Space Transportation System (STS) operational.

Description

The Space Shuttle was the first operational orbital spacecraft designed forreuse

Reuse is the action or practice of using an item, whether for its original purpose (conventional reuse) or to fulfill a different function (creative reuse or repurposing). It should be distinguished from recycling, which is the breaking down of ...

. Each Space Shuttle orbiter was designed for a projected lifespan of 100 launches or ten years of operational life, although this was later extended. At launch, it consisted of the orbiter

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, planetary exploration, ...

, which contained the crew

A crew is a body or a group of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchy, hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the ta ...

and payload, the external tank

The Space Shuttle external tank (ET) was the component of the Space Shuttle launch vehicle that contained the liquid hydrogen Rocket propellant, fuel and liquid oxygen oxidizer. During lift-off and ascent it supplied the fuel and oxidizer und ...

(ET), and the two solid rocket boosters

A solid rocket booster (SRB) is a solid propellant motor used to provide thrust in spacecraft launches from initial launch through the first ascent. Many launch vehicles, including the Atlas V, SLS and Space Shuttle, have used SRBs to give launch ...

(SRBs).

Responsibility for the Space Shuttle components was spread among multiple NASA field centers. The KSC was responsible for launch, landing, and turnaround operations for equatorial orbits (the only orbit profile actually used in the program). The U.S. Air Force at the Vandenberg Air Force Base

Vandenberg may refer to:

* Vandenberg (surname), including a list of people with the name

* USNS ''General Hoyt S. Vandenberg'' (T-AGM-10), transport ship in the United States Navy, sank as an artificial reef in Key West, Florida

* Vandenberg S ...

was responsible for launch, landing, and turnaround operations for polar orbits (though this was never used). The Johnson Space Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight in Houston, Texas (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight controller, flight control are conducted. ...

(JSC) served as the central point for all Shuttle operations and the MSFC was responsible for the main engines, external tank, and solid rocket boosters. The John C. Stennis Space Center

The John C. Stennis Space Center (SSC) is a NASA rocket testing facility in Hancock County, Mississippi, United States, on the banks of the Pearl River (Mississippi–Louisiana), Pearl River at the Mississippi–Louisiana border. , it is NASA ...

handled main engine testing, and the Goddard Space Flight Center

The Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) is a major NASA space research laboratory located approximately northeast of Washington, D.C., in Greenbelt, Maryland, United States. Established on May 1, 1959, as NASA's first space flight center, GSFC ...

managed the global tracking network.

Orbiter

The orbiter had design elements and capabilities of both a rocket and an aircraft to allow it to launch vertically and then land as a glider. Its three-part fuselage provided support for the crew compartment, cargo bay, flight surfaces, and engines. The rear of the orbiter contained the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), which provided thrust during launch, as well as the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS), which allowed the orbiter to achieve, alter, and exit its orbit once in space. Its double-

The orbiter had design elements and capabilities of both a rocket and an aircraft to allow it to launch vertically and then land as a glider. Its three-part fuselage provided support for the crew compartment, cargo bay, flight surfaces, and engines. The rear of the orbiter contained the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), which provided thrust during launch, as well as the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS), which allowed the orbiter to achieve, alter, and exit its orbit once in space. Its double-delta wing

A delta wing is a wing shaped in the form of a triangle. It is named for its similarity in shape to the Greek uppercase letter delta (letter), delta (Δ).

Although long studied, the delta wing did not find significant practical applications unti ...

s were long, and were swept 81° at the inner leading edge and 45° at the outer leading edge. Each wing had an inboard and outboard elevon

Elevons or tailerons are aircraft control surfaces that combine the functions of the elevator (used for pitch control) and the aileron (used for roll control), hence the name. They are frequently used on tailless aircraft such as flying wings. ...

to provide flight control during reentry, along with a flap located between the wings, below the engines to control pitch. The orbiter's vertical stabilizer

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, sta ...

was swept backwards at 45° and contained a rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

that could split to act as a speed brake. The vertical stabilizer also contained a two-part drag parachute

A drogue parachute, also called drag chute, is a parachute designed for deployment from a rapidly moving object. It can be used for various purposes, such as to decrease speed, to provide control and stability, as a pilot parachute to deploy ...

system to slow the orbiter after landing. The orbiter used retractable landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for taxiing, takeoff or landing. For aircraft, it is generally needed for all three of these. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, s ...

with a nose landing gear and two main landing gear, each containing two tires. The main landing gear contained two brake assemblies each, and the nose landing gear contained an electro-hydraulic steering mechanism.

Crew

The Space Shuttle crew varied per mission. They underwent rigorous testing and training to meet the qualification requirements for their roles. The crew was divided into three categories: Pilots, Mission Specialists, and Payload Specialists. Pilots were further divided into two roles: the Space Shuttle Commander, who would seat in the forward left seat and the Space Shuttle Pilot who would seat in the forward right seat. The test flights, STS-1 through STS-4 only had two members each, the commander and pilot. The commander and the pilot were both qualified to fly and land the orbiter. The on-orbit operations, such as experiments, payload deployment, and EVAs, were conducted primarily by the mission specialists who were specifically trained for their intended missions and systems. Early in the Space Shuttle program, NASA flew with payload specialists, who were typically systems specialists who worked for the company paying for the payload's deployment or operations. The final payload specialist, Gregory B. Jarvis, flew onSTS-51-L

STS-51-L was the disastrous 25th mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program and the final flight of Space Shuttle ''Challenger''.

It was planned as the first Teacher in Space Project flight in addition to observing Halley's Comet for six day ...

, and future non-pilots were designated as mission specialists. An astronaut flew as a crewed spaceflight engineer on both STS-51-C and STS-51-J

STS-51-J was NASA's 21st Space Shuttle mission and the maiden flight of Space Shuttle ''Atlantis''. It launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on October 3, 1985, carrying a payload for the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), and landed at ...

to serve as a military representative for a National Reconnaissance Office

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is a member of the United States Intelligence Community and an agency of the United States Department of Defense which designs, builds, launches, and operates the reconnaissance satellites of the U.S. f ...

payload. A Space Shuttle crew typically had seven astronauts, with STS-61-A

STS-61-A (also known as Spacelab D-1) was the 22nd mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program. It was a scientific Spacelab mission, funded and directed by West Germany – hence the non-NASA designation of D-1 (for Deutschland-1). STS-61-A was th ...

flying with eight.

Crew compartment

The crew compartment comprised three decks and was the pressurized, habitable area on all Space Shuttle missions. The flight deck consisted of two seats for the commander and pilot, as well as an additional two to four seats for crew members. The mid-deck was located below the flight deck and was where the galley and crew bunks were set up, as well as three or four crew member seats. The mid-deck contained the airlock, which could support two astronauts on anextravehicular activity

Extravehicular activity (EVA) is any activity done by an astronaut in outer space outside a spacecraft. In the absence of a breathable atmosphere of Earth, Earthlike atmosphere, the astronaut is completely reliant on a space suit for environme ...

(EVA), as well as access to pressurized research modules. An equipment bay was below the mid-deck, which stored environmental control and waste management systems.

On the first four Shuttle missions, astronauts wore modified U.S. Air Force high-altitude full-pressure suits, which included a full-pressure helmet during ascent and descent. From the fifth flight, STS-5

STS-5 was the fifth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the fifth flight of the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. It launched on November 11, 1982, and landed five days later on November 16, 1982. STS-5 was the first Space Shuttle mission to deploy comm ...

, until the loss of ''Challenger'', the crew wore one-piece light blue nomex

Nomex is a trademarked term for an inherently flame-resistant fabric with meta-aramid chemistry widely used for industrial applications and fire protection equipment. It was developed in the early 1960s by DuPont and first marketed in 1967.

...

flight suits and partial-pressure helmets. After the ''Challenger'' disaster, the crew members wore the Launch Entry Suit (LES), a partial-pressure version of the high-altitude pressure suits with a helmet. In 1994, the LES was replaced by the full-pressure Advanced Crew Escape Suit

The Advanced Crew Escape Suit (ACES), or "pumpkin suit", is a full pressure suit that Space Shuttle crews began wearing after STS-64, for the ascent and entry portions of flight. The suit is a direct descendant of the U.S. Air Force high-alti ...

(ACES), which improved the safety of the astronauts in an emergency situation. ''Columbia'' originally had modified SR-71

The Lockheed SR-71 "Blackbird" is a retired Range (aeronautics), long-range, high-altitude, Mach number, Mach 3+ military strategy, strategic reconnaissance aircraft developed and manufactured by the American aerospace company Lockheed Co ...

zero-zero ejection seat

In aircraft, an ejection seat or ejector seat is a system designed to rescue the pilot or other crew of an aircraft (usually military) in an emergency. In most designs, the seat is propelled out of the aircraft by an explosive charge or rocket m ...

s installed for the ALT

Alt or ALT may refer to:

Abbreviations for words

* Alt account, an alternative online identity also known as a sock puppet account

* Alternate character, in online gaming

* Alternate route, type of highway designation

* Alternating group, mathem ...

and first four missions, but these were disabled after STS-4 and removed after STS-9

STS-9 (also referred to Spacelab 1) was the ninth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the sixth mission of the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. Launched on November 28, 1983, the ten-day mission carried the first Spacelab laboratory module into orbit.

...

.

The flight deck was the top level of the crew compartment and contained the flight controls for the orbiter. The commander sat in the front left seat, and the pilot sat in the front right seat, with two to four additional seats set up for additional crew members. The instrument panels contained over 2,100 displays and controls, and the commander and pilot were both equipped with a

The flight deck was the top level of the crew compartment and contained the flight controls for the orbiter. The commander sat in the front left seat, and the pilot sat in the front right seat, with two to four additional seats set up for additional crew members. The instrument panels contained over 2,100 displays and controls, and the commander and pilot were both equipped with a heads-up display

A head-up display, or heads-up display, also known as a HUD () or head-up guidance system (HGS), is any see-through display, transparent display that presents data without requiring users to look away from their usual viewpoints. The origin of t ...

(HUD) and a Rotational Hand Controller (RHC) to gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis. A set of three gimbals, one mounted on the other with orthogonal pivot axes, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain independent of ...

the engines during powered flight and fly the orbiter during unpowered flight. Both seats also had rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

controls, to allow rudder movement in flight and nose-wheel steering on the ground. The orbiter vehicles were originally installed with the Multifunction CRT

CRT or Crt most commonly refers to:

* Cathode-ray tube, a display

* Critical race theory, an academic framework of analysis

CRT may also refer to:

Law

* Charitable remainder trust, United States

* Civil Resolution Tribunal, Canada

* Columbia ...

Display System (MCDS) to display and control flight information. The MCDS displayed the flight information at the commander and pilot seats, as well as at the aft seating location, and also controlled the data on the HUD. In 1998, ''Atlantis'' was upgraded with the Multifunction Electronic Display System (MEDS), which was a glass cockpit

A glass cockpit is an aircraft cockpit that features an array of electronic (digital) flight instrument display device, displays, typically large liquid-crystal display, LCD screens, rather than traditional Analog device, analog dials and gauges ...

upgrade to the flight instruments that replaced the eight MCDS display units with 11 multifunction colored digital screens. MEDS was flown for the first time in May 2000 on STS-101

STS-101 was a Space Shuttle mission to the International Space Station (ISS) flown by Space Shuttle '' Atlantis''. The mission was a 10-day mission conducted between 19 May 2000 and 29 May 2000. The mission was designated 2A.2a and was a resuppl ...

, and the other orbiter vehicles were upgraded to it. The aft section of the flight deck contained windows looking into the payload bay, as well as an RHC to control the Remote Manipulator System

Canadarm or Canadarm1 (officially Shuttle Remote Manipulator System or SRMS, also SSRMS) is a series of robotic arms that were used on the Space Shuttle orbiters to deploy, manoeuvre, and capture payloads. After the Space Shuttle ''Columbia' ...

during cargo operations. Additionally, the aft flight deck had monitors for a closed-circuit television

Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of closed-circuit television cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signa ...

to view the cargo bay.

The mid-deck contained the crew equipment storage, sleeping area, galley, medical equipment, and hygiene stations for the crew. The crew used modular lockers to store equipment that could be scaled depending on their needs, as well as permanently installed floor compartments. The mid-deck contained a port-side hatch that the crew used for entry and exit while on Earth.

Airlock

Theairlock

An airlock is a room or compartment which permits passage between environments of differing atmospheric pressure or composition, while minimizing the changing of pressure or composition between the differing environments.

An airlock consist ...

is a structure installed to allow movement between two spaces with different gas components, conditions, or pressures. Continuing on the mid-deck structure, each orbiter was originally installed with an internal airlock in the mid-deck. The internal airlock was installed as an external airlock in the payload bay on ''Discovery'', ''Atlantis'', and ''Endeavour'' to improve docking with Mir

''Mir'' (, ; ) was a space station operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, first by the Soviet Union and later by the Russia, Russian Federation. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to ...

and the ISS, along with the Orbiter Docking System. The airlock module can be fitted in the mid-bay, or connected to it but in the payload bay. With an internal cylindrical volume of diameter and in length, it can hold two suited astronauts. It has two D-shaped hatchways long (diameter), and wide.

Flight systems

The orbiter was equipped with anavionics

Avionics (a portmanteau of ''aviation'' and ''electronics'') are the Electronics, electronic systems used on aircraft. Avionic systems include communications, Air navigation, navigation, the display and management of multiple systems, and the ...

system to provide information and control during atmospheric flight. Its avionics suite contained three microwave scanning beam landing systems, three gyroscope

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining Orientation (geometry), orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in ...

s, three TACAN

A tactical air navigation system, commonly referred to by the acronym TACAN, is a navigation system initially designed for naval aircraft to acquire moving landing platforms (i.e., ships) and later expanded for use by other military aircraft. It p ...

s, three accelerometer

An accelerometer is a device that measures the proper acceleration of an object. Proper acceleration is the acceleration (the rate of change (mathematics), rate of change of velocity) of the object relative to an observer who is in free fall (tha ...

s, two radar altimeter

A radar altimeter (RA), also called a radio altimeter (RALT), electronic altimeter, reflection altimeter, or low-range radio altimeter (LRRA), measures altitude above the terrain presently beneath an aircraft or spacecraft by timing how long it t ...

s, two barometric altimeters, three attitude indicator

The attitude indicator (AI), also known as the gyro horizon or artificial horizon, is a flight instrument that informs the pilot of the aircraft Orientation (geometry), orientation relative to Earth's horizon, and gives an immediate indication of ...

s, two Mach indicators, and two Mode C transponders

In telecommunications, a transponder is a device that, upon receiving a signal, emits a different signal in response. The term is a blend of ''transmitter'' and ''responder''.

In air navigation or radio frequency identification, a flight trans ...

. During reentry, the crew deployed two air data probes once they were traveling slower than Mach 5. The orbiter had three inertial measuring units (IMU) that it used for guidance and navigation during all phases of flight. The orbiter contains two star tracker

A star tracker is an optical device that measures the positions of stars using photocells or a camera.

As the positions of many stars have been measured by astronomers to a high degree of accuracy, a star tracker on a satellite or spacecraft may ...

s to align the IMUs while in orbit. The star trackers are deployed while in orbit, and can automatically or manually align on a star. In 1991, NASA began upgrading the inertial measurement units with an inertial navigation system

An inertial navigation system (INS; also inertial guidance system, inertial instrument) is a navigation device that uses motion sensors (accelerometers), rotation sensors (gyroscopes) and a computer to continuously calculate by dead reckoning th ...

(INS), which provided more accurate location information. In 1993, NASA flew a GPS

The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based hyperbolic navigation system owned by the United States Space Force and operated by Mission Delta 31. It is one of the global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) that provide geol ...

receiver for the first time aboard STS-51

STS-51 was a NASA Space Shuttle Space Shuttle Discovery, ''Discovery'' mission that launched the Advanced Communications Technology Satellite (ACTS) in September 1993. Discovery's 17th flight also featured the deployment and retrieval of the S ...

. In 1997, Honeywell began developing an integrated GPS/INS to replace the IMU, INS, and TACAN systems, which first flew on STS-118

STS-118 was a Space Shuttle mission to the International Space Station (ISS) flown by the orbiter ''Space Shuttle Endeavour, Endeavour''. STS-118 lifted off on August 8, 2007, from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39, launch pad 39A at Kennedy ...

in August 2007.

While in orbit, the crew primarily communicated using one of four S band

The S band is a designation by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) for a part of the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum covering frequencies from 2 to 4 gigahertz (GHz). Thus it crosses the conventiona ...

radios, which provided both voice and data communications. Two of the S band radios were phase modulation

Phase modulation (PM) is a signal modulation method for conditioning communication signals for transmission. It encodes a message signal as variations in the instantaneous phase of a carrier wave. Phase modulation is one of the two principal f ...

transceiver

In radio communication, a transceiver is an electronic device which is a combination of a radio ''trans''mitter and a re''ceiver'', hence the name. It can both transmit and receive radio waves using an antenna, for communication purposes. The ...

s, and could transmit and receive information. The other two S band radios were frequency modulation

Frequency modulation (FM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, originally for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In frequency modulation a carrier wave is varied in its instantaneous frequency in proporti ...

transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna (radio), antenna with the purpose of sig ...

s and were used to transmit data to NASA. As S band radios can operate only within their line of sight

The line of sight, also known as visual axis or sightline (also sight line), is an imaginary line between a viewer/ observer/ spectator's eye(s) and a subject of interest, or their relative direction. The subject may be any definable object taken ...

, NASA used the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System

The U.S. Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS, pronounced "T-driss") is a network of American communications satellites (each called a tracking and data relay satellite, TDRS) and ground stations used by NASA for space communications. ...

and the Spacecraft Tracking and Data Acquisition Network ground stations to communicate with the orbiter throughout its orbit. Additionally, the orbiter deployed a high-bandwidth Ku band radio out of the cargo bay, which could also be utilized as a rendezvous radar. The orbiter was also equipped with two UHF

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter ...

radios for communications with air traffic control

Air traffic control (ATC) is a service provided by ground-based air traffic controllers who direct aircraft on the ground and through a given section of controlled airspace, and can provide advisory services to aircraft in non-controlled air ...

and astronauts conducting EVA.

The Space Shuttle's

The Space Shuttle's fly-by-wire

Fly-by-wire (FBW) is a system that replaces the conventional aircraft flight control system#Hydro-mechanical, manual flight controls of an aircraft with an electronic interface. The movements of flight controls are converted to electronic sig ...

control system was entirely reliant on its main computer, the Data Processing System (DPS). The DPS controlled the flight controls and thrusters on the orbiter, as well as the ET and SRBs during launch. The DPS consisted of five general-purpose computers (GPC), two magnetic tape mass memory units (MMUs), and the associated sensors to monitor the Space Shuttle components. The original GPC used was the IBM AP-101B, which used a separate central processing unit

A central processing unit (CPU), also called a central processor, main processor, or just processor, is the primary Processor (computing), processor in a given computer. Its electronic circuitry executes Instruction (computing), instructions ...

(CPU) and input/output processor (IOP), and non-volatile

Non-volatile memory (NVM) or non-volatile storage is a type of computer memory that can retain stored information even after power is removed. In contrast, volatile memory needs constant power in order to retain data.